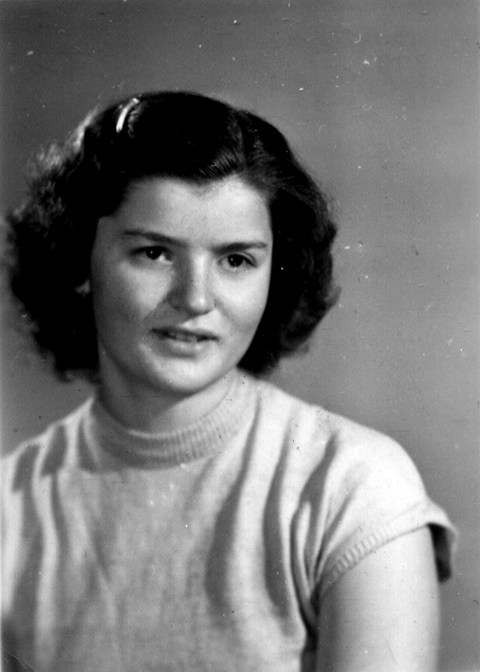

Edit Martha Novak – As I Remember

At work operating a drill

How October 23rd started I can’t recall but I imagine it must have been like any other. At the time I was employed by the Small Engine and Machinery Factory (Kismotor és Gépgyár) located in Buda. I must have put in a regular day of work there operating a drill.

Following my daily routine, after finishing work I went on to Móricz Zsigmond High School to attend an evening lecture in pursuit of my high school diploma. As soon as I reached school I became aware of a flurry of excitement. It was there that all of us students were informed that demonstrations were in progress on both sides of the city.

We heard that there were a number of points or demands that had been drafted by the university students and presented to the government. It was upon these points that the demonstrations were based. Among the points was the demand that the Soviet troops leave our country and that Imre Nagy be reinstated as our prime minister.

Classes cancelled

There was an announcement that classes were now cancelled and we were told that a group was being formed to join up with the people who were demonstrating. We students eagerly went to show our solidarity to the cause. We all started to walk across the Margaret Bridge. As we proceeded, our numbers kept growing as more and more people joined up. I most distinctly remember an incident that took place in front of the Parliament. As we stood there our numbers kept swelling and all of a sudden we all started to demand in unison that Imre Nagy present himself and talk to us. We started to chant: “We want Imre Nagy!” “To hell with Gero!”

At first it was an unknown person who came to the balcony and tried to reason with our gathering, but since we didn’t let up on our demand, Imre Nagy finally did appear on the balcony to address us.

As we stood there listening to his speech a rumor broke out about some shooting taking place in front of the Radio building. At this point I felt somewhat drained and decided to start on my long walk home. Of course the streetcars were not running, nor were the buses.

On that day-October 23rd-a bloody Hungarian revolution started and it seemed that we had won our freedom from the Russians. This freedom was regretfully short-lived, however. It lasted only approximately seven days. But during this time even many of the Russian soldiers who were stationed in Hungary sided with the revolutionaries. Imre Nagy became our prime minister as freedom reigned. Unfortunately it did not last long since the Soviets under the leadership of Khrushchev sent over several divisions. Its soldiers were told that they were to crush the bourgeois revolution, when in reality they were killing the workers and students of the country.

While the fighting took place the workers were on strike everywhere. Of course the factory where I worked was also closed. At this time my family lived in Budaõrs. We could not regain our right to live in Budapest even though our 1951 deportation ended in l953 shortly after Imre Nagy became prime minister for the first time. Regretfully he was soon pushed out of office by the Stalinist-oriented group of communists. On November 4th, with the onslaught of a second wave of Russian troops, the fate of the revolution was sealed. On the previous evening General Pál Maléter, the head of the Hungarian Army, was invited to Russian headquarters for a discussion but was arrested during the course of the night.

Stay or go?

Now that everybody realized that we freedom fighters would lose against the tremendous odds, people began to think of leaving the country. My oldest brother Frank was in a forced labor battalion at the time. He was working in a coal mine at Komló. As the revolution was being overturned he too decided to flee the country but not before coming back with a couple of his friends, each of them with the intention of taking others with them. In Frank’s case it was the oldest of his three younger brothers, Peter. When I heard of their escape plans, I too wanted to leave with them. Frank, on the other hand, did not want to take on the responsibility since my sister and I were even younger than Peter and girls. He said we should stay-“Just think what might happen if the Russian soldiers were to catch you at the border.” So there I was, temporarily resigned to my fate, but not for long. About five days later a neighbor’s daughter, nine years old, came over in the morning to tell my sister that by eleven a.m. that morning she was leaving her home with the intent to escape. Her companions were four young men. Now it was my sister Klára’s turn to declare that she was going to join a group and escape, whereupon I said to my mother that of course I must also join them. Now poor mother was beside herself since our father was stuck in Buda in the stable with his horses to look after and could have no say in the matter. She realized that our future would be better served if we were to leave, yet she also realized that should we fail all the blame would rest on her shoulders. She tried to persuade us to stay because of the danger involved, but seeing our determination she was powerless. Thus the saga of our escape began.

At the Budaõrs train station we hopped on the platform of a freight train carrying frozen meat. We were exposed to the rigid winter climate. As the sun set, one stop before the station of Gyõr our train came to a halt. Our companions found out that the carriages wouldn’t go any further but the engine itself would go on to Gyõr. Its engineer agreed to let us ride in the caboose by sharing the space with the coal. During this time the railroad personnel were doing everything they could to help escapees reach the border.

At Gyõr we boarded a regular train. Now we had a different challenge ahead of us. We were afraid to buy tickets since it would give away our intended destination, yet not having them was also risky. Therefore we ended up dodging the conductor by going from one car to the other. In the meantime the men from our group obtained valuable information on how we should proceed in our escape. They befriended a makeshift guide who advised us to get off the train one stop before Hegyeshalom, at Levél, and offered to be our personal guide from there on. He told us that the Russians were especially active at the Hegyeshalom train station. They regularly met the incoming trains looking for would-be escapees to catch.

Onward

Once we left the train station of Levél, our guide led us into a barn filled with cows where we hid for a while since even here the Russians did searches. About a half an hour later our guide returned for us. The first part of our journey took us through some cornfields; as we passed among their dry stalks the crunching noise took an additional heavy toll on our nerves. We also passed through open fields with haystacks, where we kept worrying that tanks might be hiding on the other side. Now and then we would stop by these haystacks for cover. We were always ready to hit the ground at a moment’s notice in case of danger. As we walked on and on in the moonlit night our guide suddenly turned to us and said that he could not go any farther with us. He told us that from now on we should just aim for the huge reflector lights far in the distance. He said that once we got there we would be in Austria! We continued on with our cautious trudging until suddenly we heard a voice. Now we were sure that we had been caught. Luckily one of our companions spoke German and, as it turned out, soon our despair gave way to tremendous joy. We stayed in camps for a couple of months, first near the border and then in Innsbruck. On January 15th we were able to fly over to the United States via a U.S. Army plane under the established special visas that were granted to Hungarian refugees.

Looking back now I cannot help wondering at times if it would not have been better if we could have stayed in Hungary, if the West could only have helped us to achieve our goal then and avoid more bloodshed and all the terror that awaited our compatriots for another thirty three years.

Edit Martha Novak

She arrived in the United States on January 15, 1957, received her high school diploma in Schenectady New York, her B.S. in Pharmacy from Southwestern State University in Oklahoma, and her M.S. in Institutional Pharmacy Practice from St. John’s University in New York. She is married to a fellow 56-er, Charles Farkas. They have four children: Evelyn, Miklos, Elizabeth, and Maria.