Dr. Alfonz Lengyel – Released from Prison in Time for the Revolution

On September 1, 1956, I was released from the prison of the communists. As I arrived at the train station in Budapest, my friend, Erwin Baktay, was on hand to meet me. From the station I went home to Szentkirályi Street. In front of our building, I ran into our former cook, who took one look at me and fled, terrified, making the sign of the cross. I ran after her. Though she did her best, her girth and age did not allow her to outrun me. I took hold of her arm and asked why she was afraid of me. “I’m Alfonz Lengyel,” I said, “in the flesh.” The cook’s mouth turned purple; she shook with fear. Finally, she realized that I had not come to take her with me into heaven, where she wasn’t ready to go yet.

She calmed down and learned that I had not died, and I was not a ghostly spirit pursuing her. She told me that my Father had died the previous Christmas, and only my Stepmother lived alone in the apartment. She also told me the reason she had been so frightened at the sight of me: my Father had paid 1500 rubles in exchange for the information that I had been shot dead while trying to escape from prison. As it turned out, my poor Father had to pay for false information.

The next day I had to report to the police. They gave me two letters: one from the prison authorities, stating that I was obligated to pay them for the six years’ worth of housing and food they had provided during my years of imprisonment. The other was from Dr. Laci Kardos, Director of the Hungarian National Museum – he informed me that I had a job as adjunct at the museum’s folk art collection.

As soon as I got myself together, I went to the Museum, where Dr. Kardos, my former boss, greeted me with great affection. He had heard that I had not given in to my prison interrogators, and was happy to hire me in his museum. He assigned me a room full of books and said that I should, for the time being, just read and learn rather than work. While in prison, I had kept up my studies. As a way to keep myself alive, I was constantly reviewing my college and law school studies. But after the years of physical labor in the mines under horrific conditions, the respite at the museum was welcome indeed.

October 23

All of my museum co-workers – though they did not dare say the traditional “Isten hozott” (God be with you) greeting – were very gentle with me, sometimes patting my shoulder. One day, the Director telephoned me from out on the street. He told me not to leave the museum until he personally gives me the okay. The Secret Police and Ministry of the Interior had permitted the students to hold a demonstration at the Petõfi Statue, but he believed it was a trap – he expected the official policy to switch overnight from Stalinist communism to De-Stalinized communism. He reminded me that I had recently been let out of prison, and, as a former officer under Horthy, I was suspect. Even if the communists themselves are organizing their own revolutionary transformation, he said, they might still try to identify scapegoats to blame for the “Revolution.”

An hour later, Kardos telephoned again. But this time, he was ecstatic: “Come, Alfonz,” he said, “this is now OUR REVOLUTION!” By the time I made it from the Museum on Könyves Kálmán Avenue into the city, the student demonstrators were chanting their slogans in front of the Radio building. Since my Stepmother lived in a building just behind the Radio, I started off in that direction and saw the crowds. The first guns were fired. Those nearest the entrance of the Radio building ran inside, followed by a crowd, including me. I spent that night at my apartment on Szentkirályi Street.

I heard on the Radio that two major areas of conflict were at Corvin Köz and Moszkva tér. I started off in the direction of the communist book store, and there I saw people carrying the books out of the store and burning them in great piles. I recalled the many examples of book-burning throughout history. We had, naturally, always condemned book burning as a crime – yet now, somehow, I felt that these were not books being burnt, but rather instruments that took people’s freedoms away; these books were the ideological instruments for keeping people enslaved. So I joined the crowd in burning the books.

We heard that smaller groups at the above locations clashed with armed security forces, and that political officers in civilian clothes were on the streets to report on developments, as well as to sow confusion among the freedom fighters. But practically the entire population joined the Revolution – even those who were communists, for many had joined the party under duress; others had realized they did not want this kind of communism. Many of these were like the communist I met at the prison hospital who had become a communist out of a belief in its ideals, but found it a dead end.

Of course, there were some workers from the Csepel part of the city who had been adherents of National Socialism, then – in 1945 – switched their allegiance to international communism. These, too, were disappointed, and so on October 23, 1956, they went out onto the streets to drive out the Soviet forces and their treacherous Hungarian communist lackeys.

Freedom

During a lull in the fighting, I joined the Ervin Papp group in founding the Association of Christian Hungarian Political Prisoners. I became the interim president. The Imre Nagy government even approved the founding documents of this organization. (I later took these documents with me to the United States, and when the World Association of Former Hungarian Political Prisoners was formed, I merged our own Christian Association with that one, and became the co-President of the new organization).

Meanwhile, Pál Pálinkás, a former classmate from the Military Academy, freed Cardinal Mindszenty from his prison cell and escorted him to his Residence. (Pálinkás’ real family name was Count Pallavichini, but the communists did not approve of this title and made him change his name to Pálinkás. After the Revolution was crushed, Pálinkás was executed.)

Soon after, in connection with the show trial against Bishop Grosz, I took the Ervin Papp group up to Cardinal Mindszenty’s office. The Cardinal greeted me as an old friend (he had once administered the last rites to me after a serious military injury in Veszprém; later, in 1948, he had helped me get a job at the Ministry of Religious and Educational Affairs). Mindszenty authorized me, together with the chaplain of Budapest’s Rókus Hospital, to reorganize the Actio Catholika movement. We tried to do so over the next few days, but without success, because a collaborator priest, a remnant of the Rákosi era and head of the Actio Catholika, declared that Mindszenty is a nobody, and if we do not leave the premises immediately, he would call the State Security Police and have us removed. I told him he should call anyone he wants, but we would not leave. Then I began the job of going through the archives.

We returned to Mindszenty’s office to report on our progress. Later that afternoon, I went down to the courtyard where, to my surprise, I saw my boss, Dr. Laci Kardos. He, too, was waiting to see Mindszenty. International journalists were coming and going; the Vienna-based Caritas aid organization was also conducting extensive discussions with Mindszenty’s office. Dr. Kardos told me that Imre Nagy had sent him with a message to Mindszenty, asking him to encourage the Hungarian people to support the Imre Nagy government, which had already committed to announcing an election based on a multi-party democracy.

At that moment, I felt like I was a participant in one of Hungary’s great historic turning-points. I rushed into the office and pulled Mindszenty off to one side to give him Imre Nagy’s message. He looked at me with those knowing eyes of his and replied that he had already written his radio address, and it would be just as Imre Nagy asked, for he – Mindszenty – was fully aware of the great responsibility weighing upon him as a spiritual leader of the Hungarian nation. He added – as he did later in his radio address – that his conscience was clear with respect to his activities under both the extreme right-wing regime and the communist regime, and owed no one any apologies. (Many people at the time were making public radio announcements “regretting” their actions that had caused suffering or death to millions of people.)

November 4

The ecclesiastical leader of Actio Catholika at the time asked me to come into his office on the morning of November 4, for he had changed his mind and wanted to hand over leadership of the organization to us. Needless to say, after I heard Imre Nagy’s plea for help on the radio the next morning, I did not go to that office, for the same fate would have befallen me as befell Imre Nagy’s Parliamentarians who were summoned to negotiate with the Soviets. As members of Parliament, they were protected by international law, yet they were killed anyway.

Kádár, who had been imprisoned under Rákosi, nevertheless agreed to take on Hungary’s leadership according to the Soviet model. Initially, he was a minister in the Imre Nagy cabinet. He even announced that Hungary was now – for the first time in its history – truly free. Yet he proceeded to betray our Revolution and had his compatriots hanged.

For a little while after the Revolution was crushed, I continued to go to work at the Museum, but after learning that freedom fighters and the released political prisoners were being rounded up, I asked my boss, Dr. László Kardos, to help me escape to the West. Dr. Kardos did help; apart from his wife, no one knew that Kardos and his friend, Attila Szigeti, helped me get out to Austria.

Kardos’s wife gave me a piece of paper with the name of a man in Vienna who was smuggling Hungarians across the border, and asked me – once I got out to Vienna – to have him bring a thank-you note back to Kardos and to Attila. I tossed the paper away and never made contact with the man. Nevertheless, a “thank you note” in my name arrived – which I had never written. Based on this forged note, Kardos, Attila and many others were arrested, some of them jailed and even hanged.

More than 40 years later, when the Soviet troops left Hungary, I went to Budapest on a visit – that’s when I learned, from one of my former prisonmates, about the existence of this “thank you note.” Upon returning to the United States, I gave a declaration under oath at the Hungarian Embassy that, while in the West, I was never in any personal or written contact with any of the individuals who were arrested in connection with the forged note. I placed a copy of this declaration in the official file on these cases. The declaration included my acknowledgement that while my statement could no longer help any of those who were arrested, it might serve to let future generations know how honest Hungarians were convicted or executed based on false and forged documents.

To the West

I left Budapest on December 13, 1956, and crossed the Hungarian border at Pamhage on December 24. I fell into the water, which then froze over my entire body. Locals found me lying unconscious in the snow; they took me home and called a doctor who beat the life back into me. I went on to Vienna, to the Caritas aid society, and told them that Mindszenty had authorized me to run the Actio Catholika movement in Budapest. They immediately put me to work as long as I was waiting to be assigned my next destination as refugee.

One day, a worker came to me in despair, saying a Hungarian girl had attempted suicide, and that I should talk to her. Naturally, I agreed. The girl told me that her fiance had just arrived in Vienna from the Melbourne Olympics, and the Austrian Government would only permit them to get married if she got written permission from her parents. Her parents, however, were dead. At this, I offered to legally adopt her and give my permission for the marriage. I even organized a very nice wedding for them. The newlywed couple went on to the United States, where, after a short while, they were divorced. So much for love unto death. I never heard from them again.

One day I went to the U.S. Embassy in Vienna, where a long line of Hungarian refugees was waiting for immigration papers. While I was standing there, a tall, skinny Catholic priest called out to me: “Alfonz, don’t you recognize me? I’m Imre Domjan from Miskolc. My Mother taught at the same school as your Aunt.” Imre (now Emerico) had gone to the West in 1933, then to study at the Vatican Gregorian Institute, where he was ordained a priest, then ended up in California. In short, the little kid I remembered had become a very tall, very thin priest. He told me he’d gotten funding from Bing Crosby to help a group of refugees come to the United States, and if I wanted to come, he’d put me on the list. I said yes, then got through my offical immigration interview. The interview occurred in Hungarian, because the Consul, Dr. László Tihanyi, was born in Hungary, became an American diplomat, and was sent to Salzburg to conduct interviews with the Hungarian refugees bound for the United States (Interestingly, 16 years later he retired from the diplomatic service and became my colleague as a professor at Northern Kentucky University).

After Salzburg we were sent to Bremerhaven. From there, we boarded the military ship “General Walker” for a very long ocean journey memorable for diarrhea and vomiting. Finally we arrived, through the Port of New York, to the Promised Land…

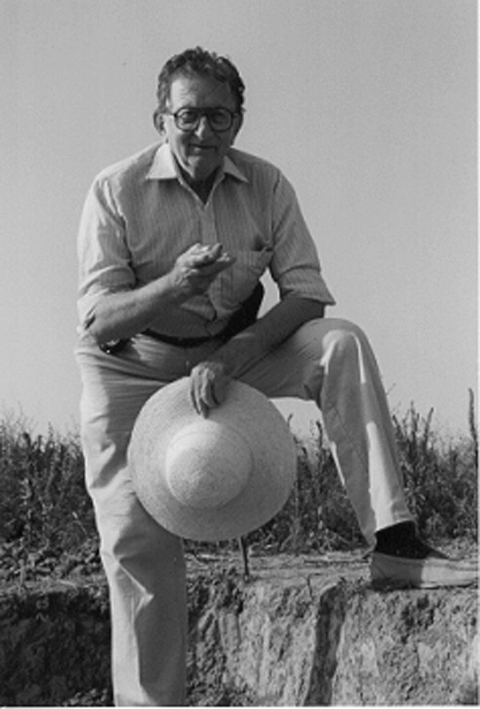

Dr. Alfonz Lengyel, RPA

A graduate of the Ludovika Military Academy, Dr. Lengyel also earned a law degree in Hungary. He earned his doctorate at the Sorbonne Institute for Art History and Archeology (Paris). He is a retired American university professor. During the 1956 Revolution, Lengyel founded the the Association of Christian Hungarian Political Prisoners. At present, he is the U.S. Director for the Sino-American Field School of Archaeology.