Lily Elizabeth Farkas nee Tersztyanszky – Released on amnesty

After 2 and 1/2 years in political prison from 1951 to 1953, I was released on the Imre

Nagy government’s amnesty. My husband, whose death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, was in Vac Prison, my parents had been deported to the country. I lived in my aunt’s tiny apartment in Budapest, where my parents joined us when the deportees were allowed to return to the Capital.

There was a special feeling in the air on that cool, autumn day of October 23, 1956. My office, where I was holding a small, unimportant job (the 17th since I was released from prison) was buzzing with good news. People, who until that day didn’t dare to trust each other, boldly volunteered information about the students who were holding meetings and preparing 16 demands from the Communist government. And now we saw groups marching down the street, carrying Hungarian national flags.

This was the day we were waiting for. We had to go and join them, forgetting the consequences of rebellious acts – leaving our desks and running down the old, worn steps of the office building in downtown Budapest.

From everywhere small groups were hurrying, forming a more and more organized demonstration. The depressed, fearful mood of the last 10 years changed almost miraculously to one of elation and hope. We smiled at each other, strangers though we were; we all knew how we felt, what we were thinking, what we were hoping for. Scissors appeared from nearby houses and the hated hammer and sickle emblems were torn out of our red-white-and green tricolors. We started singing our National Anthem and old folksongs which cried of battles and heroes of old, foretelling of new battles and new heroes to come. We marched to the Bem Square, and then on to Parliament Square. A young man read the 16 point demand the students had prepared. Freedom of speech, freedom of press, free elections and the immediate withdrawal of Soviet troops of Hungarian soil…thoughts and demands punishable with torture and long years of prison during the years before. It was unbelievable!

The huge Square was jammed with people. I had always hated crowds, but now I felt happy with all these people; we were brothers and sisters under the darkening sky, not knowing when the Secret Police or the Soviet troops would start firing on us. But we didn’t care; we were intoxicated with the simple thought of freedom!

Suddenly, as if everybody was hit by the same idea, we made torches of the daily communist newspaper – we had been forced to read and discuss it – and we stood there holding the burning papers up high.

Plans and strategies were discussed and different groups took off to the Radio Building and to the Stalin statue. I stood there and had to make an important decision. Should I go with my new friends on a hazardous venture to take up arms and cause further danger and heartache to my parents, who had suffered so much in the past years? As gunfire bursts started screaming through the dark streets, I went home. That night history was made, and the Revolution broke out in Hungary.

10 glorious days followed. 10 days full of danger, excitement, death and happiness. I roamed the streets in a euphoric state, watching the red stars being pulled off the buildings by the freedom fighters. I jumped into doorways when machine gun fire broke out over and over again. One day I wandered to Parliament Square, where the previous night Secret Police had massacred hundreds of people. The weatherbeaten old stones of the Parliament were blood-spattered and a bloody student cap was lying on the ground like a sacrifice to a cruel god.

I had a message from my husband, who with hundreds of other male political prisoners, had broken out of the infamous Vac Prison. The message said that he would return to Budapest soon.

On October 30th in the evening the doorbell rang, and there stood my husband: thin, ragged – but alive! He was dressed in clothes that had been thrown to him by the people of Vac, as he was running and yanking off his prison uniform. We hadn’t embraced each other since April 29, 1951, the night of his arrest (I was arrested a month later). Except for those terrible trials, we had only seen each other at the infrequent 5 minute visits he was allowed in the last few years in Vac.

Long into the night we talked about all that happened to us in the past 5 & 1/2 years. He told me the story how the prisoners broke out from Vac Prison. We fell asleep that night exhausted in body and soul, but full of hope for a better future for us and for Hungary.

After that horrible dawn of November 4, we didn’t want to believe that everything would be over in a few days. But we were forced to realize that we had to escape. With the return of the Communists to power, they surely would take my husband back to prison. My brother-in-law participated actively in the Revolution; they were already looking for him. So on November 21st, with him, his wife and a prison mate of my husband we said the difficult goodbyes to my parents and aunt, and slipped out of the apartment building and walked to Kelenfold train station.

We got off at the little town of Kapuvar in the cold November evening. A tall, friendly stranger came up to us and whispered,“We are leaving at midnight to the Austrian border!”

The peasants of this little border town had organized themselves in this heroic operation, saving the lives of thousands of refugees while asking nothing in return. We later learned, to our horror, that they had been brought to trial for those activities and many of them were executed.

And so we followed our leaders through the frozen marshes. When we heard patrols we had to hit the ground and wait for the all-clear signal. We crossed canals in little boats or rickety log-bridges. When rockets flared we tunneled ourselves in haystacks. We walked on; as the night passed we neared the Austrian border. Our leaders, tall gaunt working men with honest faces and brave hearts, pointed to the West.

Bonfires were burning there, lit by the Austrians, showing us to safety and freedom.

Ahead was a new beginning.

Lily Farkas

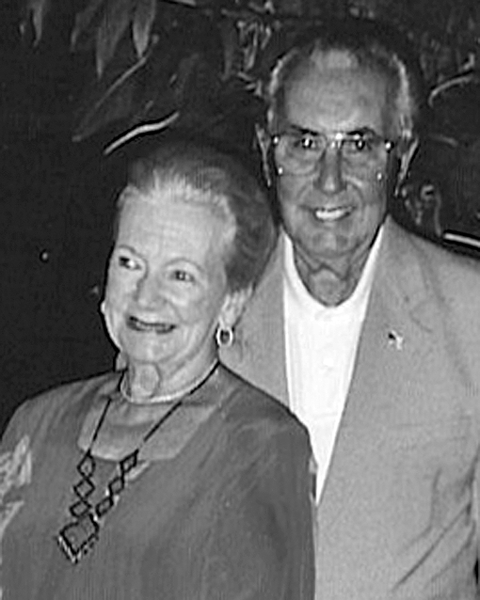

Arriving in the United States with her husband on Christmas Eve in 1956, Lily Farkas started her new life as a library assistant at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, staying in the Boston area for 37 years.She worked at Harvard University, M.I.T., Newton College of the Sacred Heart, and finally at Regis College as a librarian. She was active in the local volunteer Hungarian School and in the fundraising and organization of the construction of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution Memorial Statue on Boston’s Liberty Square. Lily Farkas has lived with her husband Imre (see his submission) in Sarasota, Florida since 1994.

Olga Vallay Szokolay – My October