Béla Lipták – A Response to Imre Nagy’s Granddaughter…

In January 2005, the Hungarian daily newspaper, Népszabadság, published an article by Katalin Jánosi, Imre Nagy’s granddaughter, who described her reaction to a recent film by Márta Mészáros, “The Unburied Dead.”

Katalin Jánosi was a small child when she witnessed the tragedies which befell her Grandfather and Father, and looks back onto those years which affected her greatly and which impelled her to follow an “inward oriented life.” In the article, she expresses her firm objections to the film, because it approaches the sufferings of Imre Nagy between 1956-58 not as a documentary, but as a feature film; also, because there is practically no mention of the sufferings endured by Imre Nagy’s associates who suffered a common fate. “I would have liked the bells to toll not just for my Grandfather, Imre Nagy, but for his companions too,” writes Katalin Jánosi.

In this writing, Béla Lipták reflects upon Katalin Jánosi’s thoughts and opinions.

On the statement by Imre Nagy’s granddaughter...

It’s hard to begin writing this, because for me it is still very strange to to consider Népszabadság as a forum for my writings. The last time I held an issue of this newspaper’s forerunner was on the night of October 23, 1956, while waiting for Imre Nagy to appear. Then, too, I needed the newspaper only to serve as a torch on the darkened square in front of the Parliament.

But the deeply affecting statement by Imre Nagy’s granddaughter, Katalin Jánosi, impels me to write. I could imagine, and it is a disturbing picture indeed, how a 4-year-old little girl must have felt as she learned about life – not playing with dolls, but rather having to see her Mother cry for days on end, and seeeing the snarling guard dogs of the Romanian soldiers. I can well understand that after such a childhood, she chose a life of internal exile, a solitary existence for a lifetime. I hope that every small Hungarian Katalin will learn to understand that their Fathers were told to remain silent about anything they cannot talk about without crying. Ferenc Jánosi, Katalin’s Father, was only obeying this rule when he remained silent about his own and his Father-in-law’s torture, and remained silent about the fact that the blackmailers could force a ”confession” from them only by threatening to murder their wives and children.

But I want to say something else, too, which little girls who were only 4 years old in 1956 could not have seen or understood: that people like Imre Nagy, Ferenc Jánosi, Mr. Szabó and István Angyal – with their heroic stance and at the cost of their lives – dealt a death blow to the communist behemoth, and it was they who launched the most important trend of the 20th century: humanity’s common fight for the freedom of each individual human being.

35 days

Like Katalin’s Father, I did not talk about certain things – not even to my children. For example, about Marika, who died of wounds from a Soviet tank in the Revolution’s defense of Móricz Zsigmond Square. Marika, just before she lost consciousness, whispered into my ear, which I had moved next to her mouth: “I have a little candy in my pocket, help yourself!” Or about Jancsi Danner, whose life I could have saved, if I had known how to shoot a gun, but I didn’t know how – I didn’t tell my children about that, either. The first time in my life that I really had an inkling of what death means was when Jancsi’s shoes had fallen off, and I tried to force them back onto his feet, which had already gone stiff, and of course I didn’t succeed. Both of them were my friends; I was next to them when they died; and they remain with me today – their memory is part of my every thought, but even today I cannot talk about them.

When your friend dies in your arms, you are changed for good. In my case, I have carried the memory of Jancsi and Marika since the age of 20. And with this memory I carry a feeling of guilt – after all, we all had the same dream, yet only they died for it. I survived the fighting, and fled. I mention this guilt not to complain – for me, it is sometimes a source of energy, which is often useful because it is combined with optimism. It is this optimism which I want to share with the Katalins of Hungary, who feel that our nation is living in an era of pessimism and self-destruction, a nation incapable of finding strength in the memory of the heroic days of 1956 – that we are incapable of finally coming to terms with our common past. But I do not believe this is the case.

During those dramatic days in 1956, I ate at the table of perfect strangers, slept as a guest in the homes of perfect strangers without ever having to spend the 20 forints in my pocket, because no one would accept any payment. I crossed the border into Austria with that 20-forint note in my pocket, because during the 35 days of the Revolution, no one would accept a penny! In every Hungarian house in the country, my tricolored armband was enough payment, and enough to make me a member of the family.

The memory of those 35 days made me an optimist for life. That experience showed me how brave, self-sacrificing and patriotic the average Hungarian person could be. In a healthy society, the average person is capable of serving as an excellent resource, an excellent building block if he believes in the country’s leaders and in the goal toward which the nation is striving. Even today – despite recent setbacks in Hungary’s political life – I am an optimist, because I know that the blood of Jancsi, of Marika, of those families who hosted me a half-century ago, could not have turned to water in their children and grandchildren! I know that the spiritual destruction that my homeland has undergone can be healed. I know that the communist system attempted to exterminate community spirit, self-confidence and patriotism from our children and grandchildren, but they attempted this in vain, because statements such as those by Katalin Jánosi do not allow, cannot allow them to succeed!

Yes, it is true that still missing from our textbooks are not just the spirit of 1956, but also the writings of such great philosophers and statesmen as István Bibó and Ferenc Deák. I know that Hungary has yet to come to terms with its past, has yet to complete a true change in the system. But I also know that Rome was not built in a day, either, and that the United States has not always followed John F. Kennedy’s wise advice: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country!” I believe that the Hungarian nation, as it stands today, will indeed be able to come to terms with its past, will be capable of healing the spiritual wounds inflicted by the communist past – after all, their forebearers were capable of much more.

Donations at the Writers’ Association

How many nations can say that boxes filled with donated money stood unguarded on the streets of their capital at the Writers’ Association headquarters? Is there any other city in the world where such a thing is imaginable? Is there any other city where the widow counted out the cost of a coffin and removed that amount, 600 or 800 forints, from the donation boxes without anyone to oversee the transaction, even as the donated banknotes continued to fall into the boxes like falling autumn leaves? No, only the people of Budapest can say this, only the Katalin Jánosis of this world can say this about the capital city of their Fathers!

At the same time, there is a genuine need for reconciliation! There is a real need for the grandchildren of prisoners sent to Romania and to the forced labor camp of Recsk, and for the grandchildren of their prison guards, for the descendents of those tortured and of those who tortured them, to finally leave the past behind and work together in peace to build a better Hungarian future. The Katalin Jánosis of this world have good reason for optimism, because this reconciliation is easily attained, but it does have some conditions. In order for society to forgive the prison guards and the Secret Police, we don’t need revenge; we need no Nuremberg trials or public hangings; we only need that the perpetrators ask pardon of the nation. That, however, is an absolute necessity.

When the Hungarian Green Party nominated me to run against Gyula Horn as a candidate, I ran into Mr. Horn in Somogy County. He reached out his hand, but I could not bring myself to shake it. I saw in his eyes that he was offended, but I saw no sign that he understood what he owes – not to me, but to his entire nation! Whoever does not ask forgiveness, who does not admit the wrong he has done, who defends the actions of the Secret Police and would sweep the murder of Jancsi Danner and others like him under the rug of history as mere “events” – cannot be forgiven.

The other necessary step, which has already been taken in several neighboring countries, is to make public the reports of the Secret Police from years past. A healthy society must be clear on its own past; only if it knows and accepts its past can a society turn its attention to the future. Everyone must know who the informant was in his apartment building; they must know what and to whom the informant submitted his reports; and they must know also that the informant himself is responsible for his crimes – not his party, nor his religious or ethnic background, nor his children or grandchildren, but he himself. Our society as a whole must realize that spying or treason are not the acts of a right-wing or left-wing person, they are neither conservative nor liberal acts – they are simply sins, for which individuals are responsible.

I believe that the soul of the Hungarian nation will be cured of the disease with which communism infected it; that the Hungarian nation will be able to close the past chapter of its history, put an end to the finger-pointing among its members and to the partisan bickering which paralyzes any possibility for national unity. When this – genuine – change of system has taken place, and when it has become evident that the former spies and secret police are to be found in every one of the current political parties, then society will also understand that a person is not a traitor because he is conservative or liberal, but because he is a despicable human being. Only then will Hungarian young people have new role models, such as Ferenc Jánosi.

Broken store windows

Let’s consider the stores whose windows were shattered as a result of the fighting during the Revolution, and the untouched inventory which no one thought to loot. Isn’t it incredible that, during those days, no one believed that looting and stealing was more important than preserving the nobility of the revolutionary cause? Isn’t it incredible that darkness fell upon the city streets, yet when the population got up the next morning, the items in the stores were still there, untouched? Is there any other nation in the world capable of such unity and self-control? Or let’s consider the horse-carts brought in to the city from the countryside, from which farmers passed out free food to those fighting on the streets of the capital. If our Fathers could behave like that, then why would it not be possible for today’s Hungarian society to join together and heal the spiritual wounds inflicted on them by the twentieth century?

Of course it is possible. After all, the spirit of the Hungarian Revolution was not quenched even after the heroic days of 1956 were over. This spirit prevailed on June 16, 1958, when we in New York learned that Kádár and his government murdered Katalin Jánosi’s Grandfather, as well as Pál Maléter, Miklós Gimes, Géza Losonczy, József Szilágyi and Mr. Szabó, and were soon to murder István Angyal and Péter Mansfeld. In response, a group of us in New York attempted to occupy the Permanent Mission of the Soviet Union to the United Nations on Park Avenue and to establish the Free Hungarian Government there. This representative body would have been headed by Anna Kéthly, the only member of Imre Nagy’s government at the time who was in the West. The New York Police foiled our plans, and I ended up in jail.

Katalin Jánosi and today’s Hungarian youth should know that in that jail cell, along with me and my brother Péter, was Gyurka Lovas who, upon hearing the news of the execution of Imre Nagy and his associates, climbed up the Soviet Union’s flagpole in front of the United Nations building, tore the Soviet flag down with his bare hands, then fell several stories onto the cement below. In the same jail cell with us was Csanád Tóth, whose journalist Father was executed for daring to research and report on how József Mindszenty’s interrogators were able to extract a statement from him – you see, Katalin, anyone(!) can be forced to give a statement! Later, Csanád Tóth became an official of the U.S. State Department; in 1978, together with Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, he brought the Crown of St. Stephen back to Hungary.

Katalin Jánosi ought also to know that not only István Angyal, executed at the same time as her Grandfather, was Jewish. Béla Fábián, who survived the labor camp at Recsk and later, as President of the Association of Hungarian Political Prisoners, posted bail for us in New York, was also Jewish. This is relevant, because the communists, though covertly, did fan the flames of anti-Semitism. One reason they let Mátyás Rákosi and Gábor Péter take power in the Hungarian Communist Party was so that the people would blame not the communists, but rather “the Jews” for the Party’s crimes. The Communists also did not fail to note that there were many “Jewish secret police” at the Recsk camp, but they did not mention that many of the Hungarian anti-communists at Recsk were also Jewish! The communist party papers were similarly silent about the fact that the Auschwitz survivor István Angyal, the heroic leader of the Tüzoltó Street freedom fighters in 1956 later executed by Kádár’s secret police, was also Jewish.

The future

I am optimistic about the future; after all, the country is now free, and today Katalin Jánosi’s generation, and their children, can read this article in the Népszabadság newspaper. Now we only need to vanquish our own selves to ensure that the Hungarian nation undergoes a healing process. For this, we must put a stop to our self-destruction and internecine fighting, and instead, use our talents the way we did for 1000 years: to be a leader in Central Europe.

I know that the Hungarian nation is capable of this – whose sons not only dealt a death blow to communism, but also brought atomic power and computers to the human race. I know that this nation will finally be capable of uniting and working for the national good. I know that the society of Katalin Jánosi is capable of this – after all, their Fathers and Grandfathers were capable of much more. I know, viewing Hungarian history in perspective, that the past 15 years represents the briefest of time periods. What are these 15 years compared to our crushing defeats at the hands of the Mongols, the Turks, and the Russian and Austrian forces in 1848? We not only survived the Mongols, Turks and Austrians, our defeats were followed by outstanding statesmen who could build upon the tremendous strength of the Hungarian nation.

I not only believe – I know – that when our consciousness has absorbed the tragedies of the twentieth century, when the spiritual wounds of communism and fascism have healed, and when the nation has reconciled with itself and again forged a unity among the spiritually and physically separated parts of the nation, then we too will follow the example of our greatest statesmen – we too can create great things. This is within reach: we ourselves need only believe that our grandchildren’s future depends upon us, and that this country really does belong to us! That is why we must take note of statements like that of Katalin Jánosi; that is why we must vote; and that is why we must, with wisdom and patience, elect as a national leader a great statesman in the best Hungarian tradition.

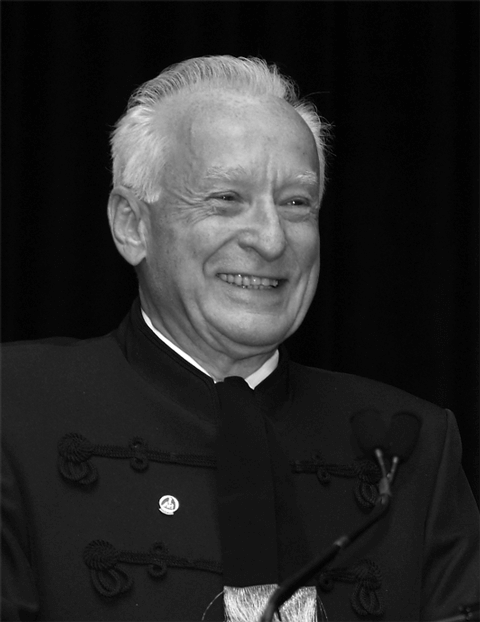

Béla Lipták

In 1956, Béla Lipták was one of the drafters of the Revolution’s “16 Points” (demands), and is now engaged in ensuring that a memorial to these 16 Points be erected for the Revolution’s 50th anniversary. In the U.S., he taught at Yale University and wrote 26 technical textbooks (three of the prefaces were written by Edward Teller). Today, Lipták is researching the technical requirements for an economy based on hydrogen-based energy.

Béla Lipták published his memories of the 1956 Revolution in a book whose Hungarian title is “35 Nap” (35 Days); the English edition is entitled “A Testament of Revolution.”

László Hámos – A Speech to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary James R. Thompson Center, Chicago, Illinois 2006. október 21.