László Papp – Personal recollections

Remembrance of the Cold War given on Veterans Day, November 11, 2005 at Rutgers University

By the time the Radio had broadcast at two o’clock on October 23 the Government’s decree forbidding any demonstrations, the column of marching students from the Technical University had already passed the Freedom Bridge and Calvin Square. Groups of students from the Eötvös University also joined in. As the crowd reached the Museum Ring the rows of marchers were wide abreast.

Our office, the Design Institute for Residential and Urban Development, was at Madach Square, above the large brick arch that was intended to be the beginning of a never-completed major boulevard through the slums of the 7th district. The secretaries of the office were cranking out leaflets of the demands, the 16 points that was passed to us from the students. The secretaries worked tirelessly on the usually restricted copy machines without any interference from the authorities.

Naturally many of the office workers joined the march. The marchers chanted slogans for freedom, independence, and removal of the Soviet military from our land. People showed support for the marchers, waving to them both from the sidewalks and from the windows. One of the greatest moments came when we reached Bem Square and saw the first Hungarian flag without the hated emblem of the Communist regime.

16 POINTS AND BLOODY CONFLICT

Later on the evening, after having heard Imre Nagy at the Parliament, I was one of a delegation chosen to present the “16 Points of the students” at the “white house,” the Communist Party headquarters near the Margaret Bridge. The people there accepted the leaflet without comment and our crowd left satisfied, believing that they succeeded. As I returned home to be with my pregnant wife, I left with a sense of hope and jubilation, but my joy proved to be short-lived.

In the meantime others brought the 16 points to the radio station to be broadcast around the country, but the situation there did not succeed as peacefully as at the “white house.” The secret police received the people’s request with bullets, then the Russian troops were called in, and the peaceful demonstration turned into a bloody conflict. My wife and I were understandably shocked and confused when we woke up the next morning hearing the sound of gunfire from the radio.

It was past 11 o’clock in the morning by the time I crossed the river to Calvin Square. By that time the combat at the nearby radio station had subsided; however, occasional gunfire continued to burst through the air. Several people were injured and a few of us pulled them back into a nearby house entrance. For a moment the street appeared quiet and normal (except, of course, for the burned-out streetcars).

Then we saw a Russian armoured car with a young Russian soldier lumped forward in the driver seat. It appeared that he was hit through the car door and apparently died instantly. “Poor boy, you had to come here to die,” murmured an older man in the crowd.

THE REVOLUTIONARY COUNCIL

As I arrived at the office we were all so charged up excitedly talking about what was happening, so no one worked all day. Suddenly there was a call for assembly in the large dining hall that accommodated all 600 workers. Someone suggested that we form a “Revolutionary Council” to replace the office’s former “triumvirate” management: the principal, the Party secretary and the personnel director. Each section of the office elected a delegate to the Council, and then much to my surprise I was elected to be the chairman of the entire Council.

The Council’s first order of business was to distribute the hated “dossiers ” kept by the personnel office on each of us. This was symbolically significant because the Council wanted to express that the old regime no longer had power. Ours was not the only such council. Spontaneously and without any direction similar “Revolutionary Worker’s Councils” were formed throughout the City. We sent a delegation to the Greater Budapest Worker’s Assembly. In addition, since we had architects and engineers, we created an advisory group to assist reconstruction work once the fight and destruction subsided. Finally we also established a schedule for providing security to our building. All in all, we felt good about our progress and hoped that freedom and order would prevail.

The following day, however, turned out to be the notorious “bloody Thursday” when Soviet tanks and secret police were firing on the crowd at Parliament Square. Fortunately I was somewhat behind the crowd so the sortie hitting the nearby Ministry of Agriculture building area missed me. The entire plaza was covered with wounded and dead people. My best friend Ferenc Callmeyer, was right up front but he also got away without injury. Later he placed bronze balls in each of the bullet holes of the building as a memorial for the fallen heroes.

FEARS FROM THE PAST

Two days later hysteria took over the crowd that assembled by the central headquarters of the Communist Party at Köztársaság (Republic) Square. The Secret Police guard resisted demands to yield to the Revolutionary Council. This resulted in the bloody lynching of four AVO officers that received so much publicity in the world media. Even though many reporters noted with awe the absence of looting or violence, this is what was put on the spreads of LIFE Magazine.

The assembled crowd started to hallucinate. They heard sounds from buried prisoners in secret cellars of the Party Headquarters. Bulldozers were summoned and they started to dig up the square.

Not finding anything, a broadcast was sent through the radio, asking anyone who may have knowledge about the building to come forward. A former member of our firm called in, with the information that the building was designed by us. So, a soldier was sent to Madach Square asking for information. I was on watch in our office and responded to the request by reviewing the building plans. I found nothing, so I called the architect and structural engineer; they confirmed that there was no secret jail or cellar.

Actually, I myself had experience with secret construction which was directed by the Internal Ministry’s design division. While I did not work on the Party Headquarters, I was part of the team designing the three residences for the top Party officials at the Béla Király (King Bela) Road. There we did get the profiles connecting to the secret areas, as it was provided by the Ministry’s staff. No such connections were given at the Party building. The whole thing proved to be nothing but mass hysteria.

Interesting to note, that while I, as an “untrustworthy class alien” had an opportunity to work on one of the most sensitive secret projects for the Party leaders in Hungary, a few years later as a refugee architect working for the most prestigious architectural firm in New York, I had the assignment to design the office for the director of the CIA.

THE SEEDS OF THE REVOLUTION

Even though the revolution was spontaneous and surprising to the world, its seeds were planted a decade earlier. After the war, as the “old world” collapsed and the fascist dictatorship was defeated, there was an expectation of a free and democratic future for Hungary. This was not to be. While the first democratic election brought a ray of hope in 1946, the “year of the turn” in 1948 marshalled in the most brutal and oppressive communist dictatorship.

The youth of the country who believed in the promise of the “shining waves” found bitter disillusionment. Even those communists who idealistically hoped for a just socialism found only betrayal. Actually they became the most vocal critics of the Rákosi regime. However paradoxical this may seem, the communist-dominated Hungarian Writers’ Union became a state within a state. Their audience had been continually increasing, and the Literary Gazette reached 450,000 circulation in a country of only 10 million. The PetŒfi Circle’s debates, voicing critical opinion, pulled together most of the leading intelligentsia.

The truth of the matter is that the collapse of Stalinism had created a political vacuum in Hungary. When the ruling classes were no longer able to govern and the oppressed classes were unwilling to live as before, the recipe for the revolution was written. Within three days the dictatorial system collapsed; even most of the privileged Party members sided with the revolution.

THE WILL OF THE PEOPLE AND THE ATTACK

For four days – from October 31 to November 3, 1956 – Hungary was free. Although Soviet forces were still in the country, they had withdrawn from the cities and the fighting had stopped. A reformist politician, Imre Nagy, was called to form a new government. The entire nation immediately recognized the Imre Nagy Government, which, knowing it had no other alternative, was ready to carry out the will of the people. And the Hungarians showed clearly what they wanted.

In his address of November 1 Imre Nagy was only repeating the desire of the people: “The revolutionary struggle fought by the Hungarian people and its heroes has at last carried the cause of freedom and independence to victory,” he said. In the spontaneously formed Revolutionary Worker’s Councils and national committees people started to develop the process of democratic self-determination. When we in the American Hungarian Student Association (ÉMEFESZ) polled our members in 1958 about their aspirations during the revolution, seventy percent agreed: “Our aim was threefold – national independence, a Hungarian socialist structure instead of Communism, and democracy.”

The glorious days of victory ended in deceit and brutal attack by overwhelming Soviet forces. Imre Nagy’s call to arms was heard at the wee hours of November 4. The next day a few of us, mostly students from the nearby Technical University, kept vigil in a third floor apartment facing one of Budapest’s major thoroughfares, Moricz Zsigmond Plaza, in the building that now houses McDonald’s. It was a mild fall day; all windows were open. “Molotov cocktails” were lined up on the windowsills. And we waited….

We were waiting for the Russians and for the Americans. Russian tanks and American diplomats. While watching the streets, our ears were glued to the shortwave radio broadcast of the Voice of America transmitting directly from the U.N. headquarters in New York. The debate of the “Hungarian situation” was going on.

We were convinced that if we could delay the Soviet’s “final solution” for a few days, the international community would prevent the destruction of our newly gained freedom. Help did not come. The Russians did come, and our building, along with most of the city, was destroyed. I am still in awe when I think of those people who lived in that apartment. They let us set up our post there even though they must have known that their home could become a target of Russian shells. As it indeed did…

CONSEQUENCES

The defeat of the revolution had tragic long-term consequences. The “compromise” which was forced by the post-revolutionary Kádár regime upon a beaten society created the often quoted “Gulyás Communism”: we let you live a little if you behave and stop resistance. Instead of national solidarity, society began to show signs of alienation, disorientation, corruption and selfishness.

Failed revolutions can, however, become historically potent forces. The Hungarian revolution proved to be the first nail in the Soviet’s coffin. It took 35 years, but the decline of the Soviet Union, a deepening economic crisis and increasing pressure by reformist groups demanding freedom, democracy and national autonomy finally prevailed. The last occupying Soviet troops left Hungary on June 19, 1991.

“The blood of the Hungarians has re-emerged too precious to Europe and to freedom for us not to be jealous of it to the last drop,” wrote the French writer Albert Camus. The thirteen days that shook the Kremlin finally triumphed.

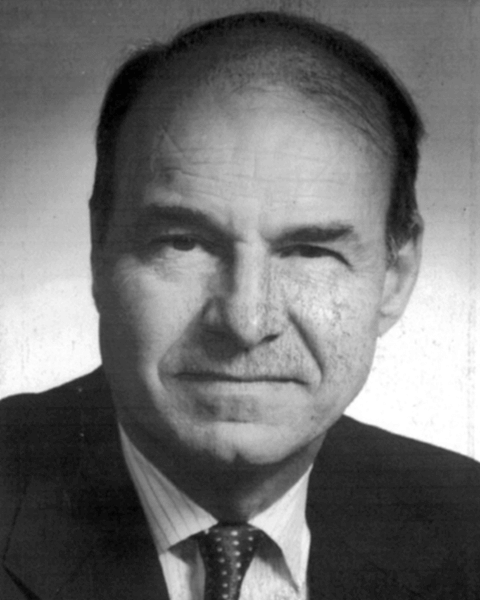

László Papp

Earning a degree in architectural engineering in 1955, László Papp worked at the Design Institute for Residential and Urban Development when he was elected president of its Revolutionary Workers’ Council in 1956. Upon emigrating to the United States, he earned first a Master’s, then a Doctor of Liberal Arts. He founded and was the first president of the United Federation of Hungarian Students, an international refugee organization. Upon retirement from his architectural firm, he beczme the executive director of the Urban Development Commission for Stamford, Connecticut. He has published in numerous professional journals, as well as writing for Hungarian-American publications.

Balázs Somogyi – A Nation Ascending