Tom Rogers Driving home from the US Legation

It was the afternoon of Friday the 26th or Saturday the 27th of October–dates are a little unclear–and a dark, cloudy, almost foggy afternoon. Anton and I left the Legation as dusk was falling, so as to be home before dark, and drove slowly through “Russian” Budapest. That was the defense circle in which the Soviets had dug themselves in most tightly; it included the Parliament, the Defense Ministry, the Ministry of Interior, all the bridgeheads on the Pest side of the river, and the area in which the Legation was situated. This section was relatively clean, as I now remember it, with little rubble on the streets, but no humans either except for the constant patrols of armored cars. We circumnavigated the tightest area, bristling with tanks, and drove down Bajcsy-Zsilinszki út to the West station and then down the “Boulevard” to the Danube. We were practically the only civilian traffic.

Face of the enemy

At the bridge, we eased between the two tanks facing the opposite side of the river, after the Russian and Hungarian army patrols had checked our papers and permitted us, as diplomats, to pass. I suppose it is easy at such a time to describe the face and feel of the enemy–they seem usually to be called “glowering” or “threatening”–and it is true these soldiers certainly did not give any evidence of camaraderie. But who can describe another’s inner feelings at such a time? Some Russians defected during the Revolution. Perhaps our “threatening Mongol” was one. Did he think he was standing on a Nile Bridge, or in Berlin, instead of over the Danube? What did the Hungarian do the day before, or the day after? How did he come, that day, to find himself patrolling the bridge with the hated enemy that his countrymen, with a unity unknown in their entire history, had just risen against? On the other hand, I suppose one has to give his momentary impressions of the enemy, subjective though these be, and not the ultimate truth of his make-up. I never saw a pro-Soviet force during the Revolution–man or tank–which struck me as anything but hostile and threatening.

We left the bridge, unguarded on the Buda side, and drove, always slowly, into Martírok utca, “Street of the Martyrs.” As soon as we turned the corner after leaving the bridge approach, the difference was noticeable: people were moving about in the streets. No armored cars, no tanks. The people were at ease, and friendly, though there were not many of them. We were now in no-man’s-land, where no Russian could come by day with impunity, but neither completely under insurgent control. This was the beginning of free Hungary.

The children

At the small square, Széna-tér, by the subway excavation, there was a road-block, manned by the free Hungarian “army” of the Széna-tér, the “gyermekek” or the “children,” later so damned and hunted by the Soviet puppet regime. The “children,” three teenagers with submachine guns, stopped us. They were tired, dirty and tense. Well might they be, since some of their group had died the night before and more were to die that night when the Soviet tanks left their daytime havens and came over in force. The “children” looked at our identification, and for the only time during the Revolution, examined our overnight bags for weapons. And as always, they and the people who crowded near asked for news, both from the other side of the river and from the world outside.

We passed on through the blockade of paving stones and three overturned railway coaches, pushed up the night before on streetcar tracks, and into the large adjoining square: Szél Kálmán-tér. Who now would have dared to use its Communist name of Moszkva-tér? This was free Hungary in reality. The crowds were thicker, as on a spring Sunday afternoon. But how was one to know then whether it was spring?

Along the Várfok ut leading up to the Vár where Anton lived, people stood by to let us pass and a few waved as we went by. We had an American flag draped over the hood of the car, although whether it was ever of any value as a safety measure I don’t know.

Flag of freedom, hope, and the future

I dropped Anton at his home, later completely destroyed by Soviet mortars, and retraced my way back down the Várfok út. As I did so–it was now almost dark–the crowds stood aside on the steep street, but this time began to clap as I drove by. We were accustomed during these days to getting nods and shouts of friendship from people on the streets, but as days passed these were already beginning to give way to such questions as: “What are you doing?” “When is America going to help?” “What is happening in the UN?” “When is Hammarskjoeld coming?” This was the only time I had seen hundreds of people stand aside and applaud the flag which to them represented freedom and hope and the future. The tears welled up.

People were clustered at the corner near our house, just a few blocks away. Marika, our children’s young nurse-maid, was standing at our door. She said there was a young man there who had been shot in the leg when Soviet tanks had tried a rare daylight foray that afternoon. Just then someone came up and asked if I would drive the wounded boy to the home of a friend a mile away. The crowd helped him into the car. He smelled of brandy; it was our brandy, I later discovered. Marika and her sister had been carrying coffee and sheets for bandages to the Széna-tér “children,” and had been asked to get a shot of something stronger for him.

The trip to his refuge was in silence; what could I say; what would he want to say? It was almost completely dark when we reached there, but a crowd gathered as I helped him out, and carried him into the house.

Letter from abroad

My 8 year old daughter wrote the following unsolicited letter to President Eisenhower: [original spelling maintained. – ed]

Dear Mr. Isenhower:

I am Elinor Rogers, 8. My father is a diplomat and we live in Budapest, Hungary, Europe. On Oct. 31 we were having our hallow’een party in the American Legation (you know, there is a war in Hungary) when suddenly a band of Hungarians gathered in front of the Legation and began crying something. Mr. Clark said they were singing their national anthem and asking us for help, but Daddy said we couldn’t because our army was in America. I am ashamed of you. Europe is our fellow country and you should help her if she is in danger. Even if you came half across the country and then lost, you would at least have glory. I wish America wasn’t so rich. It’s getting badder every year. If I were the President, I would change a lot of things in America. I wish I could give some of America’s richness to Europe, so they would be even. Europe will never be freinds with America, if you don’t help now. Please do. If you don’t, I’ll never like you again.

Elinor

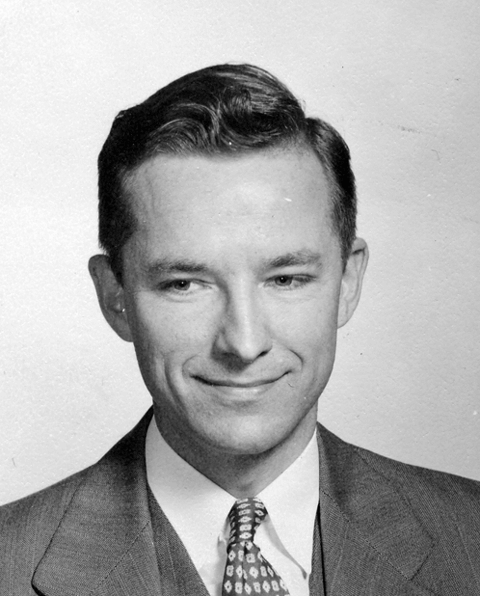

Tom Rogers

Originally from South Carolina, he graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1942 with a degree in physics, hoping to be a meteorologist. He attended M.I.T. as an Air Corps cadet and served as a weather forecaster in the North Atlantic. After the war he worked for the Foreign Service, serving in Germany during the Berlin Blockade. He was in the US Legation in Budapest from 1953 to 1957, serving as its First Secretary. He later served in Argentina, Ecuador, and Pakistan. He has 4 grown daughters and still maintains yearly contact with other former members of the 1956 Budapest US Legation. He currently lives in Mechanicsburg, PA, and hopes to spend the 50th anniversary in Hungary.

His daughter Elinor grew up to be a bilingual English-Spanish reading teacher currently living in Madison, Wisconsin. Even now she vividly remembers the events that moved her to write the letter, and still recalls a Hungarian song from her childhood, “Mennybõl az angyal.” She has not yet received a reply to her letter.

Olga Vallay Szokolay – My October