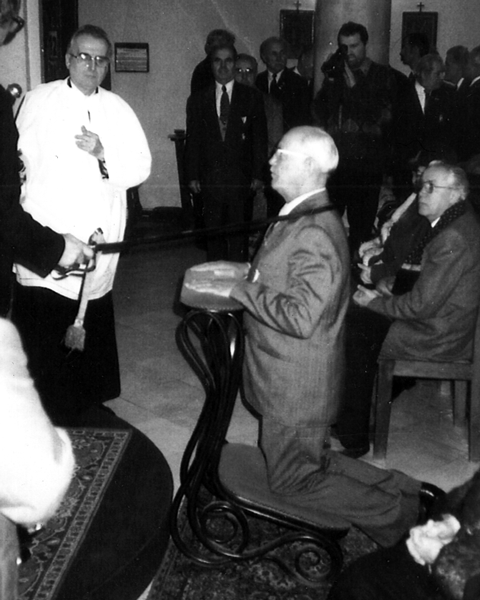

Amadé Kis Commander of Revolutionaries on Móricz Zsigmond Square

On October 23, 1956, the Hungarian nation awakened to the most glorious day of its history. The nation – having had enough of decades of slavery, physical and spiritual assaults and terror – shook off its chains and turned against its oppressors. As in 1848, the nation’s youth took the leading role in the unfolding Revolution and freedom fight. The nation wished to live free in its own country and to be rid of its oppressors.

University students called on young people throughout the country to join a peaceful demonstration. But within 24 hours, this demonstration was transformed into an armed uprising. After Ernõ Gerõ delivered his radio speech, in which he referred to the patriots as “riff-raff,” he ordered troops to fire on them.

At this time, I was living on Móricz Zsigmond Square, where small groups of people were gathering, as they were throughout the city. Everyone was discussing Gerõ’s speech, which made our blood boil – and how we should react. As I walked among the people, a truck from the Lamp Factory, loaded with weapons, drove up. It had brought ammunition for the crowd, which was, as yet, uncertain about what to do. Those in the truck told us that gunfire had broken out in several parts of the city between the Secret Police and the patriots. At the same time, a large group of students, bearing arms, arrived from the Technical University to join the crowd, which had started to organize an uprising.

Shortly afterward, another group of about 60 students from a nearby Technical University dormitory also arrived to join the crowd. The hastily organized rebels occupied the building at Number 10 Móricz Zsigmond Square. With the agreement of the residents, a group of 4-5 rebels took up their positions at each of the windows of the upper stories, so as to have a view of the neighborhood and to intervene if necessary. To maximize the safety of the local population, I suggested that we organize ourselves for the fight. The first step was to survey the block from a tactical point of view, as the open square was easily approached from several directions.

Organizing the defense

We agreed on how to defend the square and how many people to delegate to each task.

Our first task was to prepare to block the enemy vehicles as much as possible. So we removed the cobblestones of the pavement and created roadblocks. On the rest of the pavement, we tossed greased cobblestones to make the pavement slippery. Next, we started making Molotov cocktails.

The battle was not long in coming. The soldiers of the enemy Soviet forces and the Secret Police murderers attacked the square from all sides. Naturally, we joined the battle and fought off the attacks, with mixed success. The fighting varied in intensity – sometimes it was more violent, at other times quieter.

Unfortunately, many of the revolutionaries were wounded or killed, but the same could be said of the other side. During each lull in the battle, we tended to the wounded or took them to the nearby hospital. We buried the dead, temporarily, in the ground next to the statue in the center of the square.

Our sources reported that the Secret Police were firing at the entrances of the Technical University, and one student was killed during the battle. Also, the attackers fired a cannon into the textile store at one corner of the square, which immediately burst into flames. I personally witnessed the Secret Police drag out two 11-12-year old boys from the basement of the neighboring building, shoot them without a word, and toss them into the burning store. Then the murderers ran from the scene. We pulled the two boys out and brought them to the hospital on Tétényi Street, but their lives could not be saved. Later I learned that they were brothers, who had not even participated in the fighting.

One striking example of the people’s cooperation and unity was that people from the surrounding countryside came into the city – in cars and in horse-drawn wagons – bringing us food, which we then distributed equitably. In addition to the food, they brought us assurances of solidarity: “We are with you! Keep it up, boys!”

The battles raged intensively until November 2. On November 3, the fighting stopped. Taking advantage of the break, we drove out to the Lamp Factory in the city’s Soroksár section to get more weapons and ammunition.

At dawn on November 4, we heard a tremendous volley of gunfire and the sound of tanks roaring down the road. The attack resumed on all sides. The tanks fired, and we fired back. Using Molotov cocktails, we destroyed six of the cars which had supplied ammunition to the enemy tanks. Afterward, a deathly silence.

Hopelessness

Surrounded by enemy forces, we saw that taking up the fight against the much stronger enemy was a hopeless task, and would result in our certain and meaningless death.Throughout the city, hearing the news on the radio, the youthful revolutionaries laid down their arms and slowly dispersed. However, in some parts of the city, the bloody and embittered fighting continued.

The days of the crushed Revolution and freedom fight were followed by the years of terror: the searches for revolutionaries, prison sentences, executions. János Kádár promised amnesty for underage freedom fighters, both those in Hungary and those hiding abroad. He did not keep his promise; once they reached legal adulthood, he sent them to the gallows.

For several months after the Revolution’s bloody defeat, I hid out in several different locations. Finally, I decided one day to return home to my apartment in Budapest’s Csepel district. I planned to return after dark, assuming I would not be seen, but I was wrong. It was 11 p.m., but the Secret Police arrested me.

I was taken to a military headquarters in Zsombolyai Street, where I suffered horrible treatment. They branded me an enemy of the people, a counter-revolutionary, and beat me bloody. I retained barely an ounce of strength. The same day, they pushed me into a car and took me to the police station on József Street. There were more interrogations, followed by another terrible beating, because I would not sign a document that would have betrayed my associates. From here, the car took me to the internment camp at Tököl. On 3-4 occasions, they took me back to the city for interrogations, trying to get me to identify people, but they were not successful.

Unbroken

I spent two and a half years in the camp at Tököl. Even after I was freed, I spent two more years under police surveillance. I can only thank God that I am still alive. My commitment to the Hungarian nation and my love of our country has remained unbroken, but I can never forget the horrors and treachery I lived through.

[This statement was published in the Newsletter of the Csemõ Civic Circle (October 1, 2004, Volume II., No. 3.)]

Amadé Kis

The fourth child in a large family of nine, Amadé Kis was schooled in Csepel early on and performed his military service at a local garrison in Budapest. He was later taken prisoner of war at this location. In 1956, he acted as the commander of the freedom fighters at Móricz Zsigmond Square and as a result of this role, was later arrested and held in the Tököl Internment Camp for two years. Kis married Ida Melczner in 1979. He passed away in October 2004 and is buried in the Fiume Road Cemetery, in Parcel 57, dedicated to Heroes of the 1956 Revolution. This article was submitted to “56 Stories” by his brother, Ferenc A. Kis, of Cleveland, Ohio.

Francis Laping – An Epitaph for Heroes*