Ország Tibor – My father and grandfather were both gendarmes

It started like any other ordinary weekday. Tuesday we awoke to a cool autumn morning in the 8-th district of Budapest, when I started to walk to school on Prater Street, which was next to the Corvin theater. We lived on Üllõi street in the direction of Kalvin square. I didn’t have the slightest idea how this day would end.

In the preceding days, my classmates and teachers discussed the topics of the evolving conditions in unusual tones; they were freely expressing ideas regarding the removal of the Soviet occupation forces, free elections, freedom of press, those topics that in the not too distant past would have resulted in serious consequences. I was almost 13 years old, but I was fearful in hearing such conversations. The regime’s brutality was still fresh in my memory. Only three years prior, the agents of the National Security Authority (AVH) in Zalaegerszeg beat my father to death, and to this day I still don’t k now where his grave is. This occurred only because he was a gendarme prior to and during WW-II. Similarly in 1954-55, when I lived with maternal grandparents, our home was confiscated which took an entire lifetime to accumulate. This too, because my grandfather was also a gendarme, although retired, but without pension because that was also confiscated.

Chestnut puree

After school around two o’clock, my mother sent me down to the pastry shop on Museum Boulevard for chestnut puree, which was seldom available. When I stepped out of the building, I was greatly surprised at the sight of a seemingly endless crowd marching down in the middle of Ulloi street toward Kalvin square from the direction of Jozsef Boulevard, stopping all traffic. At first I thought it was some kind of celebration, or the usual self praising communist party event which had no interest for me. However, from within the ranks, two or three protesters ran to the front of the procession with a large green wreath, and continued the steady peaceful march.

I got excited at this sight, moreover because I did not hear the usual speeches of over-achiever worker accomplishments, praises of Stahanovist results or other similar party propaganda. They were mostly young, but older workers, white collar professionals and people of all ages marched along. I went along with them to Kalvin square, where additional crowds merged from many other directions, their numbers just grew. Climbing onto electric poles in various locations on the square, young orators loudly announced that the destination is the Joseph Bem monument, where they intend to proclaim their solidarity and support of the Polish university and labor movement of the recent past, which was silenced by the Polish Communist authorities. Stemming from this, they too had requests, which they started announcing from elevated protrusions, and passed out fliers to the people. From somewhere in the crowd a few national flags appeared complete with the regime’s hammer and sickle crest, which was shortly cut out of the flags and the crowds proudly waved the flags with holes.

As the march started again toward the city center, I realized that there is no chance for pastry shop and chestnut puree, since practically all shops and offices were closed because all their employees were on the streets. Surely my mother must have been wondering what was keeping me this long, and I thought it best to hurry home. I explained what I saw on the streets. She could hardly believe it possible without intervention by the police or the AVH (national security authority). Then she directed me to do my homework, since protest march here, protest march there, tomorrow is school and the homework must be done.

Foreign and domestic radio broadcasts

Naturally, I couldn’t concentrate on my studies. The afternoon’s events occupied my mind. As I was thinking about them, my memories took me back to the prohibited short wave radio broadcasts from the free west for years, and up to the recent past, that people quietly tuned in and huddled around behind closed windows for years. Of those that I knew who listened, took those transmissions for gospel truth. My favorite was the scout program because I was still in the seventh grade, and we had no scouting there. Aside from that, I was also keenly interested in political issues. To this day the transmitted encouragements still ring in my ear: ….don’t tolerate the tyrannical communist oppression….stand up against the oppressors….if you take the first step, we’ll be there to help you….etc.

As the neighbors and other tenants of the building started arriving home from work with various delays they brought news of gradually evolving developments. By now we turned on the local radio, but the transmissions did not coincide with the neighbors’ reports. The radio talked of counterrevolutionaries, scoundrels and system disrupters, but we knew that this was completely different. Now the people spoke in unison against the regime. The radio gave directives for the people to return home from the streets, and for all to remain within the houses.

On this first evening, out on the balcony after dark I heard what sounded like shots. I wasn’t sure, but it could have been small arms fire. I remember wondering…. Is it the police? The AVH? … Later during the night the frequency of these sounds increased. I didn’t know yet, but these first sounds probably came from the Radio building, which was only few blocks from us, on the street next to the Museum.

Next morning

On the morning of the 24th the continual rumblings of heavy armored vehicles, the sound of steady gunfire and explosions filled the air in front of the house and in the neighborhood. Under no circumstances was it possible to go out on Ulloi street. Well, I thought, there is no school today, the delight of all children, although my homework was more or less complete. Above all a strange feeling of excitement never felt before came over me. Is this possible? The people stood up against the regime? They took up arms?

Some of the bravest of the neighbors sneaked in and out, brought fresh news which immediately spread through the residential building. There is a full blown revolution raging throughout the city. People are dying in large numbers, last night they fired into the protesting crowd by the Radio building, and in front of the Parliament. The military has been activated along with other armed authorities, but at this time we didn’t know, only later, that Russian occupation forces were also called out. The radio constantly directed the freedom fighters to lay down their arms and they would receive amnesty. The government reassured the public that order has been virtually restored, but no one should go out on the street. Periodically they played the Hungarian National Anthem. I heard this for days. The days blended into each other. The sounds of constant weapons blasting, the fragmented series of automatic machine gun fire, the way bullets and projectiles sliced through the with whistling sounds around our house forever got etched in my memory. We heard as the tanks frequently rumbled past our house, stopping every so often, and with earth shaking thunder fired on some target.

My mother implored me not to set foot out on the street, because if I get killed in the gunfire she was going to give me a beating that I’ll never forget. I didn’t need to be frightened; there was plenty to be afraid of. But curiosity is also a strong motivator, and periodically I braved to stick my head out the main gate of the building to see “what the thunder is going on”. I peaked out to see better as the tanks approached from the Kalvin square, as they passed our house they stopped for a moment, each fired a shot in the direction of the Boulevard, but almost in the same moment I saw the smoke trailing fiery rain come down on them from the upper windows of the houses. And then, to get while the getting is good, those that could, immediately escaped into the side streets, others accelerated forward out of my sight into the smoke filled, foggy mist. Other times I overheard as armed freedom fighters passed the gate and were planning their next tank encounters.

Potato and cabbage rations

After about three days our food supply started to dwindle. We had only purchased enough for a day or two, because we only heard of refrigerators, but had never seen one. Now we had to carefully ration our supplies since it was uncertain how long we would have to be without. On about the fourth day, one of the residents got word that in the neighboring side street a truck had arrived from the farming regions with some food that they were passing out to the people. I didn’t need another invitation, since the sounds of battle were not in the immediate neighborhood, but came from some distance, I ran down to the street with a little satchel, and I found the TE-FU truck from which I also received a little cabbage or potatoes. I am not so sure anymore what it was, but whatever it was, we were all very grateful. Everyone expressed their gratitude for whatever they received. The farmers cheerfully passed the supplies with kindness, and did not take any money for it. I had never experienced anything like that in the past.

Promises from the West

One of the sub-renters in our building was a colonel prior to WW-II. He was most vocal declaring that the armed conflicts would soon be over; because the armed forces from western nations are due to arrive any time now, because we all heard their radio messages from the west…didn’t we…, and they said that they will be here if we only start it. The Westerners are not like the Communists, they don’t lie, we can trust in them, we can be confident we’ll see them soon. It would be ridiculous to think that little Hungary could effectively take on the Soviet Union, and no one could expect that a small country would rise up against such overwhelming power, that would be pure suicide. The Soviet Union would never tolerate any so called Soviet ally trying to use its muscle, to rebel, and to take up arms in the interest of separating. Everyone knew well the Soviet methods, since the Soviets had many opportunities to introduce the Hungarians to their methods in WW-II and the years after. This kind of armed opposition could only be conceivable with foreign assistance. And they promised. … we waited….but no one came. But no one speaks of this out loud anymore. Some say it is impolite to bring up accusations against a nation who gave us asylum and whose bread we are eating. They say it will not change the past no matter how much we bring up these issues. I could understand that no help arrived, but then why did they promise not only prior to the start of the revolution, but even during the battles they incited the freedom fighters to hold out for only one or two more days, because help was on the way. It is a lame explanation that those radios were not official representatives of the governments which they discussed, because those same governments provided the financial support for those radio stations. I didn’t know then and most likely no one over there did, that during those excruciating days the American administration had officially conveyed to Moscow that America has no intention of intervening in the Hungarian conflict, and that America does not consider any nation rebelling against Moscow its friend. Is it then possible that this is the reason that the departing Soviet occupation forces turned around and came back many times re-enforced? Would the last falling freedom fighter throw his life away in the hopeless knowledge that the western incitement to hold out was nothing but lies? Now there is silence about this. Are we the ones again that have to be ashamed for mentioning this?

Remnants of the battles

It must have been around October 28-29, when the heavy thunder of the battle seemed to subside, so my mother and I went down to the street. We started in the direction of the Great Boulevard (József and Ferenc Körút). At the intersection of Üllõi Street and the Boulevard in all directions we came upon the remains of such destruction that I am unable to describe in written word. The endless junkyard of destroyed tanks, armored vehicles, ammunition carriers, and a great variety of war machinery were scattered like broken toys revealing bitter but glorious battles. Some of the corpses have not yet been removed, some, probably Soviet solders, lay burned black and shriveled under tanks and armored vehicles, with disproportionately large steel helmets next to the small shriveled up heads. Ammunition and expended shells were scattered by the thousands throughout the city. Rows of once substantial six story residential and administrative buildings demolished from the roof to the ground. Not only in one place, but throughout the city, wherever we walked. In some places corpses, dusted with white lime to prevent the spread of disease, lay on sidewalks or in the street, a few in military uniforms more in civilian garments. In a shot-up trolley an unfortunate passenger’s body lay across the isle covered with lime and flowers. We had to step over the body, since it was impossible to go back, do to the curious line of people following from behind. We walked the city for a day or two, and could not believe our eyes, how such a beautiful city could be laid to ruin. One day in the vicinity of Koztarsasag square we were alerted by some yelling, about some AVH agents hiding out. Some shots could also be heard, and people were yelling to stay down, to keep from getting hit. We thought it better to completely back away from Koztarsasag square in order to stay out of a possible crossfire.

Next to a wall, passers by were tossing money into an unguarded box to benefit the needy. No one asked who will receive this money and no one took any out. At one place, pieces of wood were assembled in a shape of a human and dressed in Soviet uniform, complete with canteen and an unusually dark piece of bread in a mess kit. True to the reputation of Soviet solders, several stolen wrist watches were on its arm, and I noticed, some were still running. On the buildings I saw only the imprints of the torn off, despised red star, and hammer and sickle symbols. I saw painted slogans, such as “Russians go home” and “Gero where are you hiding… come out now” and many others, on walls everywhere. Everywhere the flames of joy and jubilant attitudes radiated from the faces. Everyone saw the dawn of freedom, since apparently the tyrannical regime was broken. The word on the street was that the Russian troops have started to pull out.

The days seemed to melt together. I am not sure exactly when, but a day or two later in the evening someone was knocking on our door. It was my grandfather. He came from Somogy county, traveling with the most unconventional modes, on trucks, tractors, motorcycles and any way possible since the normal methods were not operational. He was thrilled to see us unharmed, and announced right away that this is not over yet. Gather the most important belongings and start back to the safety of our home town, Segesd. The next day we took on the city for one more time, viewed all that could be seen for the last time. Then from Moricz Zsigmond square, we started our journey toward Somogy county, chasing after and jumping on trucks and using all available forms of transportation.

Journey to the country

It was already late into the night when we arrived in the vicinity of Szekesfehervar, when the small convoy of trucks we were traveling on came to a halt. It turned out we had to wait for a column of Russian heavy armor to pass, traveling in the direction of Budapest, before we were allowed to continue. Finally, when we were able to continue, we made our arduous way until we reached Marcali. There we could no longer use our resourcefulness, and resorted to telephoning for a farm tractor and trailer to take us the rest of the way.

In earlier times I went to school in Segesd, and when my old schoolmates saw me, they surrounded me for first-hand news about Budapest. I told my impassioned story, but I didn’t stop there. I got the whole school frenzied, and made our protest march through the village with flags; passing out handwritten flyers, the way I saw it in Budapest. The march culminated at the town hall, where the police unsuccessfully tried to quiet us down. By the time the news of police involvement reached the end of the village, it was distorted to imply that the police were gathering the children and turning them over to Russian captivity. The panicked parents rushed to the rescue, some with farm tools still in their hands, saying, nobody is gonna touch my kid, and each grabbed their own by the hand and with gratified joy dragged them home.

Not much later we got news that on November 4th there is renewed fighting in Budapest against fresh Soviet troops, and it’s not looking good. We started seriously looking at our options for the future. For two months we deliberated. Finally after Christmas, we sadly came to the conclusion that we should depart the country to the West. The plan evolved that my mother, grandmother and I would escape. My grandfather should stay behind to transfer real estate and other property to one of his nephews. Later the state would allow him to leave, since due to his age he was viewed as a burden to the nation.

Forbidden border crossing

My grandfather established contact with a resident near the Austrian border, who volunteered to act as guide. At this late point it was not advisable to attempt an escape without help, due to the newly reestablished and reinforced border security. We didn’t say anything to anyone, and on the evening of January 12th the three of us took a train to Zalaegerszeg, where according to the plan sometime at dawn we were to meet my grandfather and our guide. But the border patrol pegged us. At the moment my grandfather entered the waiting room with our guide, they surrounded us, announced that we are suspected with forbidden attempted border crossing and ordered us at gunpoint onto a truck. We were transported to police / AVH headquarters, most likely to the building where the trail of my father’s body vanished three years prior. They separated us from the two adult men, and after some interrogation ordered us to leave with the parting words: let us not meet again. In this we were in total agreement. Outside we said goodbye to grandfather, not knowing if we would ever see him again. The four of us took a taxi to the village of our guide to await the darkness.

On the 13th , after darkness settled on the hills, we started our hike through the fields, woods and valleys, avoiding residential areas in the dark. At one point an acquaintance of our guide allowed us into his house to get a couple hours of sleep. Before dawn we continued on in snowstorms over plowed fields. Anytime we saw what appeared to be patrolling activity, we hid beneath the bushes. Closer to the border when we met other escapees, and they learned how long we hiked the fields and woods without rest, some advised us against continuing, since the border crossing was still a long and grueling journey, and it was unlikely that we would survive. We were not deterred. If we made it this far, come hell or high water, we would not quit at this point. After darkness settled on the land, once again, with our last exertion of our depleted energy, we attempted the last segment. Next to a small ditch along the path a small Hungarian and Austrian flag marked the border. I glanced back for the last time, with a tear in my eye, and with a sigh pushed onward on that cold and snowy January night……. And we arrived half dead on the morning of the15th, in a small Austrian village, a free land.

Tibor Ország

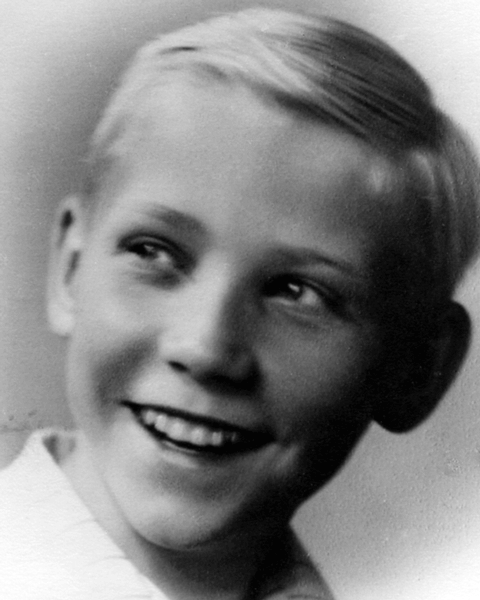

In 1956 attended the school in Prater street, next to the Corvin theater. He is a descendent of a gendarme family. In 1957 at the age of 13 he escaped from Hungary and settled in the Cleveland area. In the 1960’s he worked at a GE research and development facility. In the1970’s he established and operated a sky diving center. In the 1980’s he worked on the US Space Shuttle program in quality systems. Since the1990’s he has been an industrial management consultant. His wife is American, his daughters read and write Hungarian.

Paul Maléter – Child of the Five Year Plans